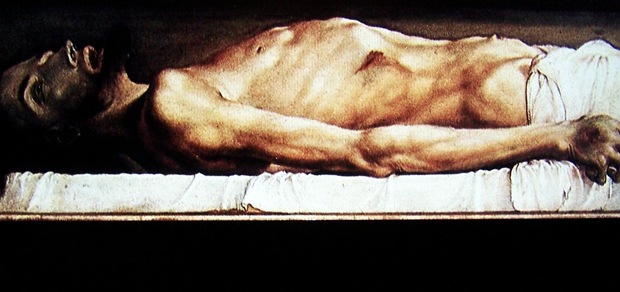

This is not a pretty painting, as this detail makes plain:

It’s not a painting one would use to argue that good art must be good looking; that it must conform to some kind of classical canons of beauty; that it should “look good” on your wall. It helps to demonstrate instead that good art must have something to say, and it must say it as powerfully as it knows how. The more fundamental the theme, and the more powerfully that theme is conveyed, then so much the better for the artwork.

By that standard, Holbein succeeds admirably. Let me explain how.

A good subtitle for this 1521 painting might be ‘A Christian Confronts Reality.’ That, at least, was how the Russian novelist Dostoyevsky felt when confronted with this naturalistic depiction of the battered Christian corpse in 1867: confronted with the horrific reality of crucifixion and its results, Dostoyevsky was struck by the importance of this confrontation for his faith, and inspired to dramatise in his next novel what that confrontation meant. Said his wife, “The figure of Christ taken from the cross, whose body already showed signs of decomposition, haunted him like a horrible nightmare. In his notes to [his novel] The Idiot and in the novel itself he returns again and again to his theme.”

The figure and its challenge became the thematic ‘pivot’ around which the whole novel revolves, in the same way (as Santi Tafarella describes it at his blog) that “Dostoevsky saw what the painting depicted as the as the ‘pivot’ on which faith or unbelief must rest.” Holbein confronts the Christian viewer with a powerful choice: One must either believe that God raised this ravaged body from the dead, and that the Christian myth, therefore, “offers hope for humanity beyond this life”; or else accept that the dead stay dead, that such an event did not and could not occur, that reality is what it is – with all that follows therefrom.

What follows may lead you either to hope, or to despair. For Dostoyevsky (and for existentialists), what follows is the despair of being “trapped” inside a “mechanistic universe.” As a character in The Idiot puts that position,

His body on the cross was therefore fully and entirely subject to the laws of nature. In the picture the face is terribly smashed with blows, swollen, covered with terrible, swollen, and bloodstained bruises, the eyes open and squinting; the large, open whites of the eyes have a sort of dead and glassy glint. . . .

Looking at that picture, you get the impression of nature as some enormous, implacable, and dumb beast, or, to put it more correctly, much more correctly, though it may seem strange, as some huge engine of the latest design, which has senselessly seized, cut to pieces, and swallowed up–impassively and unfeelingly–a great and priceless Being, a Being worth the whole of nature and all its laws, worth the entire earth, which was perhaps created solely for the coming of that Being! The picture seems to give expression to the idea of a dark, insolent, and senselessly eternal power, to which everything is subordinated, and this idea is suggested to you unconsciously. . .

Ayn Rand readers will recognise this as an eloquent description of what Rand called the utterly mistaken “malevolent universe premise” --

the theory that man, by his very nature, is helpless and doomed—that success, happiness, achievement are impossible to him—that emergencies, disasters, catastrophes are the norm of his life and that his primary goal is to combat them.

As . . . evidence of the fact that the material universe is not inimical to man and that catastrophes are the exception, not the rule of his existence, observe the fortunes made by insurance companies.

Good art need not be a thing of beauty, but it must have something to say (the more fundamental the message the better) and say what it says powerfully. This does that. You might call it an example of the power of good (but philosophically mistaken) art.

RELATED POSTS:

2 comments:

I thought you did a good job, from an objectivist perspective, of discussing the philosophical implications of the painting.

---Santi Tafarella

Thanks Santi. I appreciate that.

I was enormously impressed with how well you analysed it in so few words.

Bravo.. :-0

Post a Comment